|

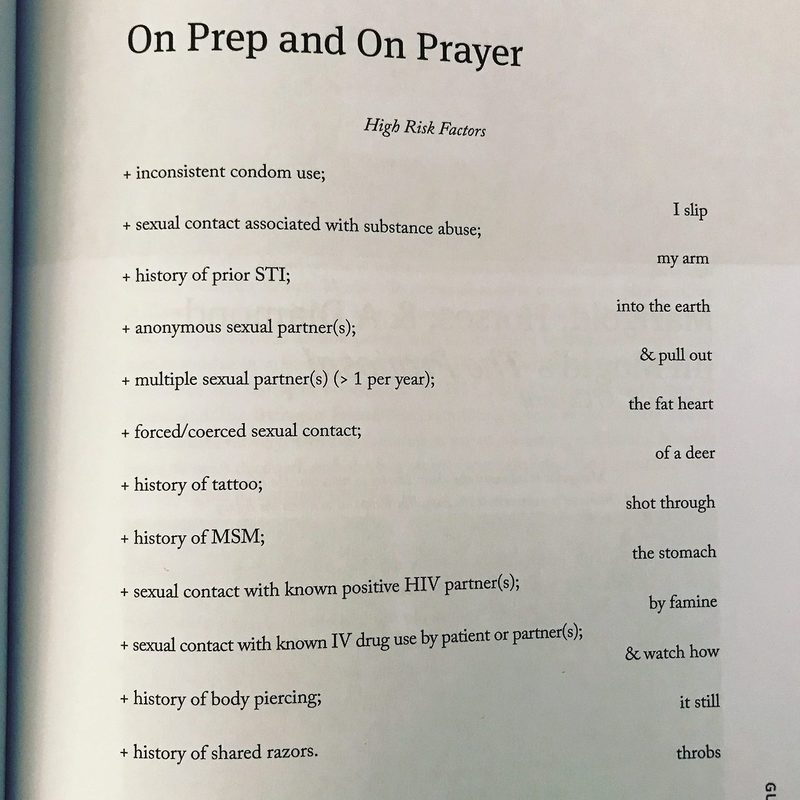

Sam Sax is an educator and writer currently based in Brooklyn, NY. Sax primarily considers himself a writer—rather than a performer, poet, or performance poet—and he is a particularly prolific one: He is the author of 4 chapbooks (All the Rage, Straight, sad boy/detective, and A Guide to Undressing Your Monsters) and 2 full-length collections (madness and Bury It, which will be published in 2018); has been published on Buzzfeed, in The New York Times, and in various poetry journals; and has received fellowships from Lambda Literary, The MacDowell Colony, & the National Endowment for the Arts. Despite his rejection of the performer label, he has also found success in the performance poetry world, earning the title of two-time Bay Area Grand Slam Champion and booking features and shows both as an individual and as a member of the poetry collective Sad Boy Supper Club. Currently, he is performing mainly in the NYC area and serving as the poetry editor of BOOAT Press. Poem 1: "On Prep and Prayer"“On Prep and Prayer” uses its dichotomous structure to highlight the speaker’s struggle to protect his health while threatened by the possibility of HIV contraction. One side of the poem consists of a list of risk factors for HIV contraction, while the other consists of a surreal narrative, in which the speaker pulls out a dead deer’s heart, which is miraculously still beating, representing the speaker’s own miraculous survival and health. The list of risk factors dominates most of the page, pushing the narrative nearly to the margin. This seems to represent the overbearing presence of the risk of contraction in the speaker’s everyday life; the anxiety over his health dominates his life and attempts to choke out his voice. However, the narrative’s short lines create a steady rhythm almost like a heartbeat, which pushes the narrative forward with a sense of determination, indicating the speaker’s effort to push forward through the health risks that pervade his life. The dichotomous structure is emphasized by the diction of each side of the poem. The list side consists of technical, sterile language. While describing the risk factors for HIV contraction, there is virtually no description of the body and mention of blood or bodily fluids. It feels clean and sterile, like a hospital room or the way one who stigmatizes HIV positivity may describe a body less at risk for contraction. It also feels stiff and lifeless, which makes the imagery of the narrative feel more vivid in contrast. Unlike the list side, the narrative is full of bodily imagery and dynamism: the arm slips and pulls, the heart throbs, and the space between the words is full of the implied gore of the deer. This imagery allows the narrative to humanize the faceless risk factors and make them feel more real and attached to an actual life. This humanization forces the reader to feel the pain behind some of these risk factors, the anxiety for one’s health, and the necessary strength one must have to continue to live and enjoy life as fear tries to hold one back. Perhaps the most compelling aspect of this dichotomy, is that it is necessary to the reader’s understanding of the poem, as neither side functions entirely independently of gives the reader the whole story. From the list of risk factors, the reader gleans and understanding of the topic of the poem—HIV contraction—as well as flashes of moments that could hint at the speaker’s lived experience and why he is at risk for HIV. The reader is never told straight out what the speaker’s individual experience with each risk factor is; they just understand that there is some connection by his narrative functions in response to the list. Meanwhile, the narrative provides a sense of the tone, leading from anxiety to a mix of shock, dull relief that peaks as the speaker and reader stare at the throbbing heart together, and a resolve that his life will continue to look and feel the way it does in the poem. The bulk of the poem happens in between the sides, in the ways that the list and narrative interact. Each new risk factor that is introduced feeds into the surreal narrative, creating a building feeling of urgency, tension, and anxiety, which the narrative resists with its steady rhythm and only hints at through the increasingly gory imagery: where once the speaker had simply reached into the earth, suddenly he grabs a heart, suddenly there is dead deer “shot through the stomach with famine,” and so on. This dynamic is finally reversed at the last line, where the speakers seems to have his revelation that in spite of everything, he is still alive and in good health. Then the heart throbs, the first hopeful image of the poem. Through the interactions of these sections, the reader does not a get a straightforward narrative of the speaker’s struggle with the risk of HIV contraction but they do get suggestions of memory set against the pulsing rhythm of the speaker’s anxiety and resilience. Poem 2: "Lorazepam"i don’t know shit about the throat of a sparrow. how it can sing & fly at the same time. this couch a sovereign object. this back, a cadillac on cinderblocks. i stood once, not for something, rather, on my way to the kitchen for something to eat. i bit into an apple, quite the achievement. i wanted to be high so lied to the doctor about my anxiety, the panic attacks began then. naming the disease made it open like a primer in my chest. wicked mouth, peeling apple after apple after reading their skins are poison, same goes for the seeds. my man is a monster, gunfire in the street. praise the demigod pharmacy for this calm blood remedy, which lets me do nothing. my back pinned to the cushion again. my body, this magnificent prison, the ceiling above bigger than any sky, one a bird might fall out of, singing as it dies. “Lorazepam” describes the speaker’s struggle with prescription drug abuse, which he seems simultaneously ashamed of and thankful for. The poem seems to tip back and forth between the speaker admonishing himself and him wanting to be vulnerable to reader and make them understand why he relies on drugs. This creates a tension between aggression and tenderness in the tone that the reader sees between the first line and the next two: “I don’t know shit/about the throat/of a sparrow.” A larger version of this happens at line 15, when the poem visibly shifts. The first line of this section is harsh and sarcastic with the speaker seeming to mock himself with “what an achievement.” However, then the poem finally dips into the vulnerability it hints at until this point. The speaker confesses to the reader, “I wanted to be high/so I lied to my doctor.” This is the only point in the poem where the speaker gives the reader a linear narrative to follow, and it provides the reader with the some context needed to understand the rest of the poem and provides the speaker the space to confess, with the spatial shift making it feel like an offshoot or a private confessional room. After this confession, the speaker seems to be less harsh towards himself.

This poem not only lurches with the tug-of-war between aggression and tenderness but also loops back into itself, imitating a circular addiction. One instance of this circular rhythm is in the movement of the speaker himself. He begins on his back on the couch, moves to the kitchen, and then ends up with his “back/pinned to the cushion/again.” A similar thing occurs in the shifted section, in which the scene opens with the speaker biting into an apple, moves away from this image to tell the story, then moves back to an unsettling image of his “wicked mouth” eating endless apples with poison skins and seeds. This looping back to the apple imagery, paired with the somewhat surreal imagery of the wicked mouth, creates a dreamlike quality of a fuzzy timeline that feels like it is looping and folding in on itself, which adds to the poem’s general drug-like haze. Finally, the poem opens and closes on the same peculiar image a bird and its ability or inability to sing and fly at the same time. In the beginning of the poem, the speaker compares himself against the sparrow, suggesting that he cannot be like the sparrow, which sings and flies at the same time, because he is sedentary in his drugged out state. This feels like an admonishment of the self and admission of shame. However, at the end a bird falls from the ceiling-sky over his prison-body, “singing as it dies.” This may indicate the speaker’s feeling that his conditions—whether that be his addiction or the conditions that caused it—are severe enough that no one could function them in them; even the sparrow can’t sing and fly at the same time in his sky, so to speak. The sparrow dies because it chose to sing rather than fly, suggesting some choice of pleasure or joy in the short time over one’s wellbeing. This may the speaker’s attempt to make the reader understand why he relies on drug abuse.

2 Comments

Jessica Cummins

10/15/2017 05:31:46 am

Jolie, I really liked what you had to say about both poems. Your insights are incredibly well developed, organized and thoughtful. I agree with you about the sterility of the list on the left side of "On Prep and Prayer." It seems really formal and cut and dry which makes a really interesting juxtaposition to the passion and animation with which the deer is described. It is almost as if the speaker of this poem believes the deer has more life than a person with HIV has. But then it is also interesting that the deer's heart is ripped out just like it must feel for a person to learn that they have a disease like HIV. Then the poem mentions the deer experienced famine and I wonder about that part too and how that related to the other side of the poem unless perhaps it pertains to abstinence somehow but I'm not sure it was really addressed.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

ENGL4302 Spoken Word Poetry & Pedagogy at LSU ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed